Harvard’s annual financial report for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2023, published today, suggests that a post-pandemic new normal is largely in place. Operating revenues rose, but less than in the prior year, when students who had deferred admission or been on leave swarmed back to campus. With operations in full swing, and wages and other costs inflating, expenses increased more rapidly. Accordingly, the operating surplus narrowed, but the University remained comfortably in the black. And the investment return on endowment assets turned positive (reversing the losses during 2022), so the endowment’s value held nearly level. Highlights include:

•Harvard recorded a $186-million operating surplus, down from the eye-popping $406-million pandemic-rebound results in fiscal 2022. The latest results punctuated a full decade of Crimson black ink, dating from fiscal 2014, when belt-tightening after the Great Recession and the first fruits of the $9.6-billlion Harvard Campaign combined to stabilize what had been a battered fisc. University revenues exceeded $6 billion for the first time.

•The endowment nearly held its own as Harvard Management Company (HMC), which is responsible for investing the assets, realized a net 2.9 percent rate of return, improving upon the negative 1.8 percent return in the prior year.

•The aggregate endowment investment gains of $1.3 billion, combined with $2.2 billion distributed to Harvard’s operating budget (and in turn offset in part by $561 million in gifts for endowment, plus other changes and transfers), decreased the endowment’s value modestly, to $50.7 billion at year-end fiscal 2023 from $50.9 billion on June 30, 2022.

The New Team’s Tone

Although the results reported today were not realized on their watch, the University’s new president and financial leaders (all assumed their current positions July 1) are responsible for the tone-setting letters that introduce the annual report.

President Claudine Gay wrote that the report “is far more than an accounting of our finances; it is a reflection of our commitment to expanding access to education and knowledge, to driving discovery and innovation, and to fulfilling our responsibility to a society that looks to Harvard for approaches and answers—for hope that tomorrow will be better than today.” As examples, she cited increased undergraduate financial aid, the role of the Axim Collaborative in extending online learning to historically black colleges and universities, and the Harvard Art Museums’ new free-admission policy—illustrations of the University’s emphasis on access, depicted on the report cover (see art above). She also highlighted research on artificial intelligence and climate change. Looking ahead from Massachusetts Hall, Gay wrote that “there is no end to what we aspire to achieve together—no end to what we can achieve together.”

The new financial-management team of Ritu Kalra, vice president for finance and chief financial officer, and Tim Barakett, treasurer (succeeding Thomas J. Hollister and Paul J. Finnegan, respectively), also focused on the larger context in which the University operates—volatile financial markets, rising interest rates; the Supreme Court decision on affirmative action in admissions—and the issues on which its scholarship and teaching can make a difference—from climate change to artificial intelligence and the new doctoral program in quantum science. Throughout, references abound to the academic mission and Harvard’s efforts to make its research, teaching, and collections accessible.

Turning to matters strictly financial, Kalra and Barakett moved beyond some of the inherent cautions of the prior leadership, whose successful stewardship during much of the past decade did a great deal to restore Harvard’s strength after the severe damage incurred during the financial panic and Great Recession of 15 years ago. That said, they briskly “acknowledge the [new] financial challenges that lie in wait”—a suggestion that the operating paradigm for institutions like Harvard may be shifting.

Foremost among these factors may be a secular change in economic conditions: “On the heels of the most substantial interest rate tightening cycles since the 1970s, the cost of capital is anticipated to remain elevated”—possibly affecting future investment returns. That is a serious matter, because endowment distributions totaled 37 percent of fiscal 2023 operating revenue (and market returns also affect substantial donors’ philanthropic capacity: current-use gifts accounted for a further 8 percent of revenue). Although hailing the “capable navigation of complicated markets” by HMC, they observe that the 2.9 percent return on investments is substantially below Harvard’s long-term return target of 8 percent—assumed to be sufficient to support distributions while preserving the assets’ value against long-term inflation. (The most recent Higher Education Price Index, for fiscal 2022, was 5.2 percent: nearly double the fiscal 2021 rate, and nearly triple the fiscal 2020 rate.)

Kalra and Barakett warned that “the costs of running a world-class university…continue to increase,” not least as research in all disciplines becomes more computational and data-driven, and as scientific discovery in particular demands ever more sophisticated, expensive equipment, facilities, and skilled staff. Accordingly, there is work to be done: “Overall expenses rose 9 percent this fiscal year, double the increase in revenue. This is not sustainable”—especially given constraints on such traditional revenue sources such as tuition after financial aid, and federal support for research. Hence a continuing focus on “prioritizing activities which most consequentially contribute to our mission” and on using “our financial, physical, and technological resources more effectively.”

The Year that Was

Revenue. Harvard’s operating revenue increased 5 percent during fiscal 2023, to $6.1 billion from $5.8 billion in the prior year (all figures are rounded).

Looking at major sources, endowment distributions (37 percent of the total) rose about $125 million, to $2.2 billion from $2.1 billion: nearly 6 percent. The increase reflects the 4.5 percent increase in the distribution per endowment unit owned by schools, approved by the Corporation for fiscal 2023, plus the increase in the number of units owned (from gifts); a similar 4.5 percent increase is authorized for fiscal 2024. (These measured increases smooth the effect of the outsized gains in the endowment’s value from fiscal 2021, when the investment return was 33.6 percent, while buffering budgets from years of negative or only modestly positive returns, like fiscal 2022 and 2023.) Although they have a far lesser effect on University revenues, other streams of investment income, totaling $217 million in the most recent year, are up smartly from a couple of years ago (an aggregate 35 percent), reflecting larger balances from schools’ retained recent operating surpluses and sharply higher interest rates on the short-term investments held in the University’s General Operating Account.

Net student income (22 percent of the total, reported after financial aid) increased slightly more than $100 million, to $1.3 billion: up 9 percent. Degree programs (undergraduate and graduate) yielded 5 percent more revenue. College enrollment, some 7,178 students in fiscal 2023, remained elevated as undergraduates who took leaves or deferred admission during the pandemic resumed their programs; the expectation is that the undergraduate cohort, normally about 6,600, will remain outsized for perhaps another couple of academic years (boosting tuition and fee income for a while longer, and perhaps aid spending, too). According to the report, fee income—board and lodging revenue—rose 11 percent, to $221 million, primarily reflecting graduate students’ return to campus housing. The real standout was executive and continuing education, which rose 12 percent, to $544 million—exceeding the pre-pandemic record, and reflecting the resumption of in-person programs. These operations may face more competition today, given other institutions’ pandemic pivot to online executive education, but Harvard’s executive education programs maintain a strong reputation across a broad array of offerings involving most of its schools, so this important source of revenue growth may well be back on track.

Sponsored support for research (17 percent of revenue) increased by $50 million (5 percent), with federal (two-thirds of the total) and nonfederal (one-third, from corporations and foundations) support growing at an equal rate. The reported growth in federal funding should be discounted somewhat, however—included in that total is a one-time grant of $25 million to reimburse prior COVID-19-related expenses.

Gifts for current use (8 percent of revenue) declined a reported $19 million, to $486 million (less than 4 percent), but that result reflects accelerated payments on pledges during prior years. Overall, such giving remains at the high level attained in the aftermath of the Harvard Campaign.

Other revenue (16 percent), a catch-all category, declined $45 million, to $793 million—about 5 percent. In fact, most line items increased, but the fiscal 2022 result was inflated by $152 million in royalties from agreements to license intellectual property, an inherently volatile item; in fiscal 2023, such revenues were a more typical $59 million.

Expenses. The University spent $5.9 billion on operations in fiscal 2023, up nearly a half-billion dollars from $5.4 billion in the prior year: 9 percent.

Salaries and wages rose $215 million, to $2.4 billion from $2.2 billion, or nearly 10 percent. About half that increase is attributable to merit increases and other adjustments for nonunionized employees, and to negotiated contracts for unionized staff. The rest reflects growth in the workforce—principally from filling positions that remained vacant at the end of fiscal 2022 when the labor market was particularly unforgiving (hiring has become marginally easier). Positions have also been added to support research, information technology, and growing operations like executive and continuing education. Employee benefits spending increased $44 million, to $628 million (up 8 percent)—essentially in line with salaries and wages. As in fiscal 2022, rising interest rates had the effect of reducing Harvard’s operating cost for pension and retiree healthcare costs, moderating the reported benefits expense. As the workforce expands at current, higher salaries (compared to prior vacancies) and pressure increases on healthcare costs, this expense merits monitoring in the future.

Other expense categories exhibiting notable growth largely reflected the resumption of full University operations and increased in-person use of facilities. Space costs rose $40 million (11 percent), as more people worked more hours on campus, and as energy prices increased. The University spent $59 million more (8 percent) on services purchased. And the grab-all other line rose by $83 million (17 percent), notably driven by a more than doubling of travel expense, to $93 million, as more people got on more airplanes and paid higher fares.

Capital spending. Harvard’s outlays for fixed assets—buildings and equipment—rose to $512 million in fiscal 2023 from $356 million in the prior year. Activity remains far below the level at the end of the last decade, when billion-dollar years were the norm. Such projects still reflect pandemic-driven disruptions in deliveries of materials and equipment, shortages of skilled construction workers, and permitting delays. And Boston-area cost inflation remains severe, particularly for highly skilled building trades. So current outlays are both lower than planned, and, in effect, buying less than anticipated. Major projects during fiscal 2023 included Adams House renewal and the fitting up of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering’s new laboratory quarters in Boston. Pending regulatory approval, Harvard no doubt would like to begin moving earth for the new American Repertory Theater facility and affiliate housing tower in Allston this academic year—a major element in refilling the construction pipeline.

The balance sheet and giving. Bonds and notes payable changed little during the year: Harvard issued $25 million in tax-exempt commercial paper (for capital spending), and $152 million in taxable commercial paper (to supplement working capital). These two short-term borrowings increased total indebtedness to $6.2 billion from $6.1 billion at the end of fiscal 2022 (after maturities and amortizations). They can perhaps be seen as temporary hedges against threatened market disruptions when it seemed possible that the U.S. Congress would neither raise the federal debt limit nor agree on even temporary federal budget measures, sowing chaos in the capital markets. Interest expense was $207 million in fiscal 2023, up from $183 million. The effective interest rate on all of Harvard’s borrowings is 4.0 percent, and the University maintains its AAA/Aaa credit ratings.

Liquid, short-term investments held outside the endowment to support operations were $1.4 billion at the end of fiscal 2023, down from $2.2 billion a year earlier (when the proceeds from $750 million of new debt issuance had not yet been deployed to pay for capital projects).

Gift receipts (in which Harvard includes nonfederal sponsored research grants) remained robust, at slightly less than $1.4 billion, down about $40 million from fiscal 2022. The $561 million in endowment gifts recorded (down from $584 million in fiscal 2022) apparently did not include the $300-million gift to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences made by Kenneth C. Griffin ’89, announced last April (to honor which the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences now bears his name), so it appears to have been reported in an earlier year. Pledges receivable (including for current use, nonfederal research support, construction, and endowment) rose to $2.7 billion from $2.6 billion in fiscal 2022. Pledges for endowment decreased about $180 million, to about $1.25 billion, perhaps representing the fulfillment of promised gifts dating from the Harvard Campaign. But other categories of pledged gifts rose significantly; among the notable gifts during the year were the $350 million in support for the eponymous research institute made by Hansjörg Wyss, M.B.A. ’65 (his fourth for this purpose), announced last October.

The Endowment

This was the sort of year that vexed managers of large, diversified endowments like Harvard’s. As common market indexes, like the Standard & Poor’s 500 and NASDAQ (up 19.6 percent and 26.1 percent), soared mostly in the second half of the fiscal year, and mostly on the gains of a very few, large-capitalization technology stocks, permanent endowments lagged behind. The more sophisticated their strategies and the more highly diversified their assets, the larger the gap.

Smaller endowments and foundations, which tend to invest principally in publicly traded securities, appear to have earned 9 percent to 10 percent returns on average during the year (stocks up, bonds down). But somewhat larger institutions appear to have realized rates of return averaging 6 percent to 7 percent, reflecting the underperformance of private equity holdings—and the larger the endowment, the greater the penalty. HMC’s CEO N.P. Narvekar explicitly warned about this possibility last October, in the wake of stupendous venture capital and private equity returns in fiscal 2021, followed by steadily, sharply rising interest rates beginning in early calendar year 2022. And indeed, during fiscal 2023, sophisticated, diversified endowments produced results well behind the 10.9 percent return on a passively invested, plain-vanilla 70/30 (global stocks and high-quality U.S. bonds) portfolio.

Among institutions with diversified investments reporting fiscal 2023 returns so far are:

•MIT, negative 2.9 percent;

•Duke, negative 1 percent;

•University of Pennsylvania, 1.3 percent;

•Dartmouth, 1.6 percent

•Yale, 1.8 percent (perhaps a surprisingly strong showing, given its near-total aversion to public securities);

•University of Virginia, 2 percent (including a negative 5.3 percent return on private equity, which accounts for 26.3 percent of invested assets, and accordingly underperforming both its model portfolio return of 12.3 percent and passive market indexes); and

•Stanford, 4.4 percent (“Strong results in most asset classes…partially offset by losses in our venture capital and growth equity portfolios, continuing a correction that began in 2022”).

Updated October 26, 2023, 4:00 p.m.: Princeton reported a negative 1.7 percent investment return for fiscal 2023.

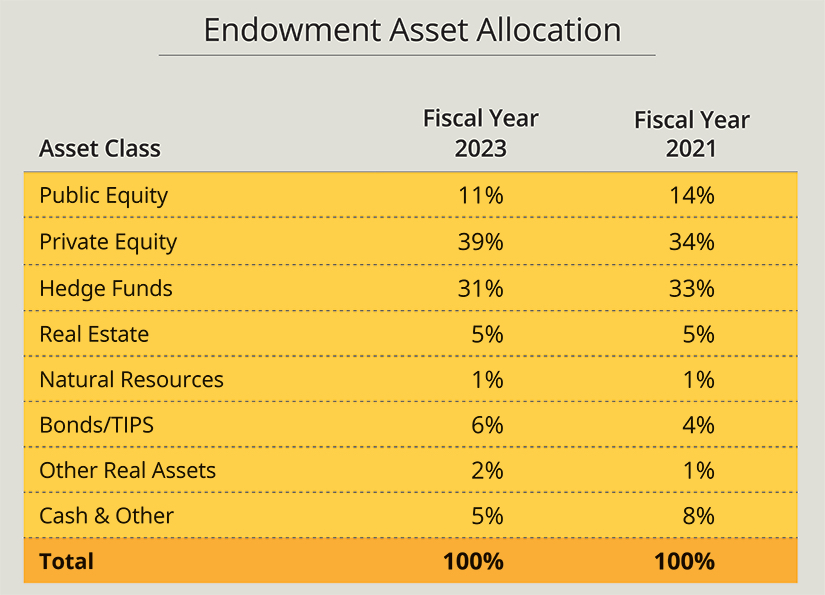

In this company, HMC’s middling 2.9 return is a relatively good showing. As the chart below illustrates, private equity accounted for 39 percent of assets at the end of fiscal 2023—up 5 percentage points from two years earlier. As reported, HMC did not report its asset allocation in fiscal 2022, and no longer reports performance by asset class. (What those data do not reflect is the radical reordering of the asset allocation from fiscal 2020, effected by the 77 percent return on private equity assets during the following year: an enormous, 11-percentage-point increase in the private equity allocation during fiscal 2021, and offsetting aggregate reductions in the relative size of the public equity, hedge fund, and other portfolios.)

During fiscal 2023, Narvekar reported in his annual report letter, returns “proved to be only slightly positive in private equity and mildly negative in venture capital/growth,” in line with his prediction last year. So, for nearly two-fifths of the endowment assets, the year was a wash. Nor could the public equity holdings overcome that effect: they are only one-quarter the size of the private investments, and they are not invested in the popular indexes. (In fact, in the past, HMC has been known to use shorting strategies tied to market indexes to hedge risk in other parts of its portfolio, and it is certainly invested in foreign and developing-market equities, some of which have lagged U.S. performance of late, and many of which are affected for reporting purposes by the relative strength of the U.S. dollar.)

Whatever penalty this strategy imposed of late, when public equities soared in the second half of this fiscal year, HMC avoided the losses associated with public equity holdings in fiscal 2022, when major indexes produced double-digit losses across the board. Similarly, the relatively large and diverse hedge-fund assets are meant, in many cases, not to be correlated to other markets or are structured to provide liquidity; in any event, they don’t represent a great deal of net equity exposure. Accordingly, if performance in that large asset category matched HMC’s expectations, it may well have had a modest effect on the endowment’s absolute return. And positive returns on cash may have been offset by negative, or nil, returns on bonds. Taken together, the result is a slightly positive return on invested assets.

Narvekar’s message seems to confirm these interpretations. Reflecting on the restructuring of HMC that he initiated after arriving in 2016, he wrote, “the alpha [risk-adjusted return over market benchmarks] generated by HMC’s manager selection has been very strong, greater than we would have anticipated”—an apparent note of satisfaction in the performance of HMC’s equity and hedge-fund investment partners. He also noted that current results have been bolstered by asset allocation: notably, the decision to “pivot from real estate and agriculture/timber to private equities” early in HMC’s transformation—decisions that seem particularly prescient today, especially given the carnage in commercial real estate assets like office buildings and retail facilities. Adjusting for Harvard’s lower level of risk tolerance compared to peers during its decade of recovery following the Great Recession, HMC’s performance has been competitive. (Peers’ stronger returns in the exceptional fiscal 2021 reflect both their greater commitment to private equity then, and their participation in investment pools several years earlier when Harvard was not involved.)

Looking ahead, Narvekar sounded several promising notes. First, although private equity valuations were not adjusted downward when public markets declined in fiscal 2022, he observed that “those private asset managers did not subsequently increase the value of their investments in the context of rising public equity markets” in fiscal 2023. Even as other observers remain cautious about private equity performance in the next few years, he seems to be suggesting that the gap between public and private valuations is now much narrower—and therefore not nearly so ominous as it was a year ago. (The apparent increase in private equity holdings, to 39 percent of assets, may be a timing issue. As the market for initial public offerings shut down in fiscal 2022 and 2023, slowing private equity managers’ distributions, they have also taken in new funds for investment based on existing commitments from limited partners, like HMC—whose unfunded private-equity commitments totaled nearly $9 billion as of June 30. As conditions normalize, it would not be surprising to see HMC’s private equity allocation drift down a few percentage points.)

He also emphasized nascent areas of HMC investment: biotechnology (public and private equities), technology venture capital, and emerging technologies to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions (where Harvard is an especially early investor).

Longer term, if outperformance by HMC’s fund managers reverts to the norm (“if the manager selection alpha attenuates,” as he put it), Narvekar pointed to two sources of strong returns in the future. The first is continued excellence in asset allocation (for example, the past decision to set up those “liquid uncorrelated funds within our overall hedge fund allocation”). The second is the recent increase in tolerance for investment risk, negotiated with the University, that underlies the planned increase in private equity holdings of late.

Although Harvard financial managers understandably focus on inflation and interest rates as they figure out how to pay the bills and borrow needed funds, HMC’s outlook may differ. In historical perspective, prior decades with interest rates at today’s levels have been conducive to decent returns on equity investments—and whatever the prevailing level of interest rates, all investment managers will have to adjust to them. If investors can earn 5 percent for risk-free holdings of short-term U.S. Treasury securities, of course, it might be cheaper for HMC to anchor the portfolio and manage risk that way rather than through elaborate hedging strategies. In that sense, the seeming rise in financial market volatility and political instability arrive at a time when HMC itself has stabilized and settled into its remade strategies, investment disciplines, asset-allocation processes, personnel, and relationships with external fund managers—and so is prepared, come what may.

In that spirit, Narvekar concluded his message by emphasizing the importance of “always keeping Harvard’s mission front of mind, ensuring that the University has the financial resources to achieve academic excellence, expand opportunities for students and faculty, and foster diverse educational experiences. I am excited to see what we will accomplish together in the years ahead.”

What Lies Ahead

By any standard, Harvard is financially sound—and therefore in an enviable position to pursue its intellectual ambitions. At the same time, those favorable conditions persist only so long as the community remembers how hard-won the institution’s current financial strength was, and applies those resources prudently in an environment of rapid economic change and great political uncertainty. An operating surplus of $186 million is not chump change—but after a year when expenses rose 9 percent, a 3 percent operating margin isn’t that much of a cushion.

The list of expensive mission-critical wants is long. The annual financial report emphasizes accessibility, and both President Gay and Ritu Kalra and Tim Barakett (for whom financial aid is a personal and fundraising passion) rightly cite the College’s increased income threshold, now $85,000, for cost-free attendance. But important peers have already raised their thresholds to $100,000—and for all the discussion of low-income students’ needs and legacy admissions, the biggest absolute gap may be for the large cohort of students from families whose incomes fall between the ends of the distribution. The recent strategic review of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences emphasizes competitors’ significant increases in fellowships (atop the punishing cost of living in Greater Boston) and begs for more financial support for students. Investments in science are only going to become more expensive. Finishing House renewal (the looming Eliot-Kirkland project) now looks like a billion-dollar item. The design, education, and public health campuses all have deferred, significant building needs. And no one has begun to tote up the costs over the next decade of retrofitting the campus at large to meet Harvard’s sustainability goals.

So there is plenty to do now and (whetting fundraisers’ appetites) in the future.

That said, the two financial leaders “thank Harvard’s faculty, students, and staff for revitalizing the campus following the pandemic, and for your vital contributions, on a daily basis, in making Harvard one of the world’s preeminent institutions.” Long may it remain so, in pursuit of its ever more vital research and teaching mission.

The 2023 annual financial report is posted at the Harvard financial administration website. Read the Harvard Gazette conversation about the financial results with executive vice president Meredith Weenick and vice president for finance and CFO Ritu Kalra here.